Some practical (and safer) tips to support teen brain development and turn a time of "peril into promise"

I've often written about the fact that teens are 'missing a piece of their brain'. It's something that I joke about with young people when I speak to them and ask them if they've ever suddenly done something quite bizarre and out-of-character and then just seconds later think to themselves, why did I do that? Without fail, almost every person in the room smiles and nods, acknowledging that, yes, they can totally relate to that experience … Strictly speaking, of course, teens are not actually 'missing' a piece of their brain, it's just that there are some important areas have not yet fully developed.

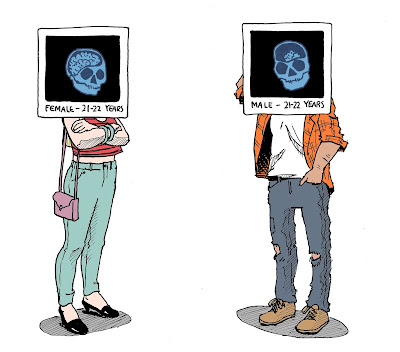

Development in the brain occurs in a back to front pattern, with the prefrontal cortex being the last area to fully develop, for females around the age of 21-22 years and for males much later (around 25-26 years at least, but recent evidence suggests that some development may continue until possibly even 35!). This prefrontal area is the part of the brain that adults primarily use when making decisions, i.e., we use reasoning and judgement and balance up the 'pros' and 'cons' before we do things. With this section not yet fully developed, teens have to rely on another area when processing information and making choices - the amygdala (the 'emotional' part of the brain). This means they are more inclined to respond to situations with 'gut reactions', rather than think through possible consequences, i.e., there is a decrease in reasoned thinking and an increase in impulsiveness (or as one writer described it – they put the "pedal to the metal without suitable brakes"). They jump into things, often well aware of the consequences, it's just that at that point the possible reward is far more important. Almost all of the decisions they make are based on the simple premise - 'if it feels good, I'll do it!'

Unfortunately, as adults we often see this behaviour as some sort of 'fault', that something is wrong with young people of this age. Certainly, adolescence can be a challenging and potentially dangerous time but as we learn more about what is going on in a teen's head, we now appreciate how important this stage of life is. As Sarah-Jayne Blakemore writes in her book Inventing Ourselves: The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain - "The teenage brain isn't broken. Adolescence is a period of life when the brain is changing in important ways: we should understand it, nurture it – and celebrate it."

I have just finished reading a wonderful book called The Power of the Adolescent Brain: Strategies for Teaching Middle and High School Students by Thomas Armstrong (it's the first book I have read in one sitting since my teens!). He provides a wonderful summary of what we know about adolescent brain development and then challenges educators to examine what is being done in the classroom and see whether it matches up. It's full of really practical suggestions and is a great read …

He identifies a number of adolescent traits, all of which send shivers down most parents' spines, and outlines their evolutionary advantage. I've written many times about the why the teen brain is 'wired' to take risks, put simply, it is an evolutionary feature to get them to 'engage in high-risk behaviour to leave the village and find a mate'. We don't see it only in humans – rodents, primates and even some birds seek out same-age peers and fight with parents. It's all about helping the adolescent to move away from their home territory. We can try all we like to fight this biology, to somehow prevent this high-risk stage of life, but it is important and helps young people to establish their own identity and find their place in the world, independent of you …

Here are the adolescent traits Armstrong highlights, along with their advantages, i.e., how they assist in helping them become fully-functioning adults:

So what can a parent do to support teen brain development and help change "peril into promise"? I've taken the adolescent traits discussed above and tried to provide some practical ideas that parents could consider introducing or use in family activities when interacting with their teen to assist in this area. They are as follows:

References

Armstrong, T. (2016). The Power of the Adolescent Brain: Strategies for Teaching Middle and High School Students. Alexandria: ASCD.

Blakemore, S.J. (2018). Inventing Ourselves: The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain. London: Penguin Books.

Joyce, A. (2017). The sex talk isn’t enough: How parents can teach teens about healthy relationships. Washington Post, May 17, accessed 9 November, 2018.

Development in the brain occurs in a back to front pattern, with the prefrontal cortex being the last area to fully develop, for females around the age of 21-22 years and for males much later (around 25-26 years at least, but recent evidence suggests that some development may continue until possibly even 35!). This prefrontal area is the part of the brain that adults primarily use when making decisions, i.e., we use reasoning and judgement and balance up the 'pros' and 'cons' before we do things. With this section not yet fully developed, teens have to rely on another area when processing information and making choices - the amygdala (the 'emotional' part of the brain). This means they are more inclined to respond to situations with 'gut reactions', rather than think through possible consequences, i.e., there is a decrease in reasoned thinking and an increase in impulsiveness (or as one writer described it – they put the "pedal to the metal without suitable brakes"). They jump into things, often well aware of the consequences, it's just that at that point the possible reward is far more important. Almost all of the decisions they make are based on the simple premise - 'if it feels good, I'll do it!'

Unfortunately, as adults we often see this behaviour as some sort of 'fault', that something is wrong with young people of this age. Certainly, adolescence can be a challenging and potentially dangerous time but as we learn more about what is going on in a teen's head, we now appreciate how important this stage of life is. As Sarah-Jayne Blakemore writes in her book Inventing Ourselves: The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain - "The teenage brain isn't broken. Adolescence is a period of life when the brain is changing in important ways: we should understand it, nurture it – and celebrate it."

I have just finished reading a wonderful book called The Power of the Adolescent Brain: Strategies for Teaching Middle and High School Students by Thomas Armstrong (it's the first book I have read in one sitting since my teens!). He provides a wonderful summary of what we know about adolescent brain development and then challenges educators to examine what is being done in the classroom and see whether it matches up. It's full of really practical suggestions and is a great read …

He identifies a number of adolescent traits, all of which send shivers down most parents' spines, and outlines their evolutionary advantage. I've written many times about the why the teen brain is 'wired' to take risks, put simply, it is an evolutionary feature to get them to 'engage in high-risk behaviour to leave the village and find a mate'. We don't see it only in humans – rodents, primates and even some birds seek out same-age peers and fight with parents. It's all about helping the adolescent to move away from their home territory. We can try all we like to fight this biology, to somehow prevent this high-risk stage of life, but it is important and helps young people to establish their own identity and find their place in the world, independent of you …

Here are the adolescent traits Armstrong highlights, along with their advantages, i.e., how they assist in helping them become fully-functioning adults:

- Risk-taking - as already discussed, this "drives them out of the parental nest and into the world"

- Sensation seeking - getting immediate sensory gratification from novel, complex and intense experiences pushes them to explore the world around them, regardless of potential dangers

- Preference for being with peers - when they are children, the adults in their lives have the greatest influence. They need to work out who they are and where they 'fit', in doing so, they start to develop relationships and affiliations with people they will spend more of their time with in adulthood, often bouncing between groups and individuals until they find who they want to be with who want to be with them

- Reward seeking - "impels them to seek, find and consume survival-essential natural rewards such as food, water and warmth"

- Romantic and sexual attraction to others - "connects them with possible mates with the potential to procreate and pass along genes to the next generation"

So what can a parent do to support teen brain development and help change "peril into promise"? I've taken the adolescent traits discussed above and tried to provide some practical ideas that parents could consider introducing or use in family activities when interacting with their teen to assist in this area. They are as follows:

- Risk-taking - 'risks' are different for different people and they don't have to involve physical activity or life-threatening situations. Don't forget that the social risks that teens make are just as important and, of course, just trying something for the first time can feed an adolescent's need for risk. Try a new physical activity as a family, e.g., go hiking, horseback riding or kayaking. If they're just not that into the whole family thing but still want to do something physical, there are so many activities that they can get involved with that are just that little bit different, e.g., indoor rock climbing, trampolining, etc. If they're not the sporty type, encourage them to join different clubs at school or try out for a drama production. For the more academic, encourage them to try out for scholarships, study overseas, or simply take up a subject or course that is a little out of their comfort zone

- Sensation seeking - this is not necessarily the same as risk-taking, which is more about balancing risk and reward, this is to do with the pursuit of sensory pleasure and excitement purely for its own sake. If your teen is prone to this behaviour, there's nothing you or anyone can do to stop them hunting that thrill out, however, it is possible for parents to provide activities that deliver exactly the same adrenaline rush but under controlled conditions, with not as much potential risk. Without a doubt one of the easiest routes is to involve them (and become involved yourself) in extreme sports. These are high-risk activities that can 'feed their need for speed' but are carried out under strict safety rules. As a family, visit an amusement park with rollercoasters, go paint-balling or anything that provides a quick thrill. Once again, if they're not into sports or physical activities, the same 'rush' can be achieved by performing in front of strangers, whether it be singing (going to karaoke) or drama (introduce them to Theatresports or the like)

- Preference for being with peers - as already stated, adolescents are trying to create their own identity. Whereas you were once the most important people in their life and your opinion had so much influence on what they thought and what they did, they now start to pull away and identify far more with their peers. It’s important to remember that you still have an influence, it's just that that influence has changed. They will want to be around their peers and gain 'peer acceptance' whenever they can - so giving them opportunities to have friends around is important. One of the best ways to do this to make your home a 'peer-friendly' place to hang out. This is not about trying to be 'friends' with your child's mates - that's just weird and wrong in about a million ways! It's also not about providing a place where they can do what they what and damn the consequences. This is simply acknowledging that their friends are important to them and allowing them to have a space where they can bring them to 'do their thing' is useful in maintaining a connection and supporting this key element of brain development. There still have to be rules and boundaries around acceptable behaviour but if you keep them close and monitor them (in a fair, reasonable and age-appropriate manner) during this time you are likely to reap the benefits later!

- Reward seeking - we know that during the teen years, young people are more likely to respond to rewards than punishment. Offering your child praise and positive rewards for desired behaviour is much more likely to get the response you are after rather than simply yelling and screaming and laying out the law. I've discussed this before but 'grounding' your teen because of poor behaviour has proven to be particularly ineffective (do you really think you can carry out the punishment and realistically, who are you punishing?). Of course, there have to be consequences for bad behaviour or breaking rules but, whenever you can, reward good behaviour. When it comes to parties and alcohol, don't just focus on what they may do wrong on a Saturday night, keep congratulating them for everything they did right. If your teen has been following all the rules, reward them by relaxing them to some extent. You don't throw them all out but acknowledge the positives whenever you can and praise them accordingly. We know their brains are wired to respond positively to reward … It is important to remember that this is not about bribing your child (although I've certainly met many parents who've tried to do that over the years!), it's about the use of positive reinforcement, something research has found teens respond better to than adults

- Romantic and sexual attraction to others - it's a brave parent who gets too involved in this area as you can't decide who your child is or isn't sexually attracted to! That said, this can be handled in a very similar way to how you deal with other peers - i.e., by making sure you maintain a connection with them and whoever they may decide to bring home and introduce to you. What is most important is to understand this isn't all about sex, it's about 'healthy' or respectful relationships' and how you support your teen's decisions to make good choices here. There's a great article from the Washington Post by Amy Joyce that provides some really useful advice for parents in this area, all of which acknowledge and support this significant adolescent trait

References

Armstrong, T. (2016). The Power of the Adolescent Brain: Strategies for Teaching Middle and High School Students. Alexandria: ASCD.

Blakemore, S.J. (2018). Inventing Ourselves: The Secret Life of the Teenage Brain. London: Penguin Books.

Joyce, A. (2017). The sex talk isn’t enough: How parents can teach teens about healthy relationships. Washington Post, May 17, accessed 9 November, 2018.

Comments

Post a Comment